The benefits of trade have been well documented throughout history. The economic case is quite straightforward. Opening up to trade allows countries to shift their patterns of production, exporting goods that they are relatively efficient at producing and importing goods at a lower price that they can’t produce resourcefully at home. This lets resources to be allocated more efficiently allowing a nation’s economy to grow. Fruits of trade can be seen in many countries. In the last 30 years, trade has grown around 7% per year on average (WTO, 2013). During this time period, developing nations have seen their share in world export increase from 34% to 47% (WTO, 2013) which at first glance seem incredible. However if we dig a little deeper, it is quickly apparent that China is the key reason for the majority of the growth and that a bulk of these developing countries aren’t benefiting fully from international trade. Why is this?

Many developing countries depend on the export of a few primary products and in some cases a single primary commodity for the majority of their export earnings. In fact, 95 of the 141 developing countries rely of the export of commodities for at least 50% of their export income (Brown, 2008). This is where the problem starts. Prices in the primary good’s market tend to be highly volatile sometimes varying up to 50% in a single year (South Centre, 2005). Often, the fluctuation of these products are out of the hands of the developing countries as they individually have only a small portion of the world supply which is not enough to affect world prices. At the same time, some shocks (ie. Weather) are unpredictable. The unstable commodity price brings uncertainty, instability and often negative economic consequences for the developing countries. This also affects the policymaking in the country as it is hard to implement a sustainable development scheme or a fiscal expansionary policy with uncertain revenue. Positive shocks do increase income in the short run however a study by Dehn (2000) found that there are no permanent effect on the increase on income in the long run. Furthermore, there is often very little scope to growth through primary products as it is very hard to increase volumes of sale. This is due to the demand being inelastic.

The over dependence on the export of primary products also causes another problem – a risk of a large trade deficit. Several studies (Olukoshi, 1989, Mundell, 1989) have shown that primary commodity prices are the main cause for the debt problems in many developing countries. In an empirical research done by Swaray (2005), he shows the main reason behind this is the deteriorating terms of trade, developing countries face. Terms of Trade is equal to the value of export over the value of import. Over time there has been a general trend of primary products falling in value. 41 of 46 leading commodities fell in real value over the last 30 years with an average decline of 47% in real prices, according to the World Bank (cited in CFC, 2005). This has occurs due to inelastic demand for commodities and lack of differentiation among producers hence making it a competitive market. The creation of synthetic substitutes has also suppressed prices. At the same time, manufacturing products (which generally developing countries tend to import) see a general rise in prices. Put these trends together, over time, developing countries have seen their terms of trade worsen. A study by CFC (2005), shows that the terms of trade have declined as much as 20% since the 1980s. This, alongside the difficulty to increase volumes of sales has meant many developing countries have a trade deficit.

According Bhagwati (1958), it is possible that this decline in the terms of trade could result in diminished welfare. In other words, growth from trade can be negative rather than positive. This can be seen in Diagram 1. Let’s say X is the export primary commodity whilst Y is the importable manufactured products. As time goes, international trade increases, growth is achieved. This pushes the PPF curve upwards. As primary commodities fall in price level relative to manufactured goods, the terms of trade deteriorates resulting in the (Px/Py) to flatten from (Px/Py)1 to (Px/Py)2. If the terms of trade deteriorate enough, the country will move on to a lower indifference curve from I1 to I2 meaning a decrease in welfare. This is also known as immiserizing growth. Although there is no evidences of this occurring yet, if terms of trade continue falling, it could occur soon.

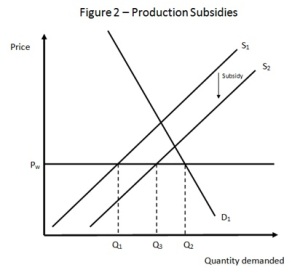

The agriculture and textiles industries, which developing nations have a comparative advantage in producing, have long been protected in developed nations. Extensive evidences from many studies show that the trade barriers of developed countries disproportionally target exports of the developing countries. Average tariffs imposed are much higher for agriculture and textiles than on other products (WTO, 2013) hence increasing the price of the imports and making them less competitive in their domestic markets. Furthermore, tariffs are increased on processed products hence it takes away the incentive for developing countries to specialize in more high valued products which is needed to simulate growth. Production subsidies are form of protectionism measures that are used by developed countries to protect their domestic industry especially the agriculture. In 2009, OECD countries spent over 255 billion US dollars alone on production supports (Bernhardt, 2010) for agriculture which accounts for 22% of gross farm receipts. As seen in Diagram 2, these supports make it hard for developing countries to compete and decreasing the demand for their exports. The subsidies shift the supply curve from S1 to S2 resulting in domestic production to go up from Q1 to Q3 whilst imports decrease from Q1-Q2 to Q3-Q2. If the impact of tariff is added in to the diagram, the quantity exported by developing countries is further negatively impacted. The exports of the developing countries that do manage to still remain competitive are often accused to be an act of dumping. Between 1995 and 2003, there were over 2068 cases of dumping (Bernhardt, 2010) of which the majority were brought up by either the US or the EU. At the same time, the US and the EU encourage excess domestic production of agriculture which is exported at prices below the cost of production suppressing world prices. Developing countries neither have the bargaining power or the financial capacity to pursue anti-dumping case against these activities. This leads to the question why are these developed countries allowed to do such things. The simple answer to this is bargaining power that the developed countries have gained through historical advantage in factor endowment and technological advance which allows them to negotiate terms that support their domestic markets. According to a study by Dimaranns and Keeney (2003), these protectionism measures as a whole have suppressed world prices by 3.5 – 5% which leads developing countries to lose 24 billion US dollars annually (Stigliz and Charlton, 2005) in the agricultural industry alone.

Reblogged this on OromianEconomist and commented:

” The benefits of trade have been well documented throughout history. The economic case is quite straightforward. Opening up to trade allows countries to shift their patterns of production, exporting goods that they are relatively efficient at producing and importing goods at a lower price that they can’t produce resourcefully at home. This lets resources to be allocated more efficiently allowing a nation’s economy to grow. Fruits of trade can be seen in many countries. In the last 30 years, trade has grown around 7% per year on average (WTO, 2013). During this time period, developing nations have seen their share in world export increase from 34% to 47% (WTO, 2013) which at first glance seem incredible. However if we dig a little deeper, it is quickly apparent that China is the key reason for the majority of the growth and that a bulk of these developing countries aren’t benefiting fully from international trade. Why is this?

Many developing countries depend on the export of a few primary products and in some cases a single primary commodity for the majority of their export earnings. In fact, 95 of the 141 developing countries rely of the export of commodities for at least 50% of their export income (Brown, 2008). This is where the problem starts. Prices in the primary good’s market tend to be highly volatile sometimes varying up to 50% in a single year (South Centre, 2005). Often, the fluctuation of these products are out of the hands of the developing countries as they individually have only a small portion of the world supply which is not enough to affect world prices. At the same time, some shocks (ie. Weather) are unpredictable. The unstable commodity price brings uncertainty, instability and often negative economic consequences for the developing countries. This also affects the policymaking in the country as it is hard to implement a sustainable development scheme or a fiscal expansionary policy with uncertain revenue. Positive shocks do increase income in the short run however a study by Dehn (2000) found that there are no permanent effect on the increase on income in the long run. Furthermore, there is often very little scope to growth through primary products as it is very hard to increase volumes of sale. This is due to the demand being inelastic.

The over dependence on the export of primary products also causes another problem – a risk of a large trade deficit. Several studies (Olukoshi, 1989, Mundell, 1989) have shown that primary commodity prices are the main cause for the debt problems in many developing countries. In an empirical research done by Swaray (2005), he shows the main reason behind this is the deteriorating terms of trade, developing countries face. Terms of Trade is equal to the value of export over the value of import. Over time there has been a general trend of primary products falling in value. 41 of 46 leading commodities fell in real value over the last 30 years with an average decline of 47% in real prices, according to the World Bank (cited in CFC, 2005). This has occurs due to inelastic demand for commodities and lack of differentiation among producers hence making it a competitive market. The creation of synthetic substitutes has also suppressed prices. At the same time, manufacturing products (which generally developing countries tend to import) see a general rise in prices. Put these trends together, over time, developing countries have seen their terms of trade worsen. A study by CFC (2005), shows that the terms of trade have declined as much as 20% since the 1980s. This, alongside the difficulty to increase volumes of sales has meant many developing countries have a trade deficit.

According Bhagwati (1958), it is possible that this decline in the terms of trade could result in diminished welfare. In other words, growth from trade can be negative rather than positive. “

LikeLike

Pingback: Trade & development: Why many developing countries seem, contrary to what the traditional theories suggest, not benefiting from international trade | OromianEconomist